Episode 9 - Insight

Awakening from the Meaning Crisis

Ep. 9 - Awakening from the Meaning Crisis - Insight

NOTE: If you’re a new subscriber to my substack, I’d invite you to start at my review of the first episode of this lecture series.

The last episode introduced the Buddha’s mythos, and started to unpack how mindfulness likely works under the hood of our cognition. We saw intimations that there are deep connections between mindfulness and the nature of our attention. We also glimpsed at the inadequacy of the “spotlight” metaphor of attention, since it doesn’t capture the rich optimization happening under the hood.

This episode goes deeper into the structure and nature of attention. It’s actually a rich avenue of active cognitive scientific research. In this episode, John attempts to summarise some of this work. More specifically, to integrate it into an account of how mindfulness leads to the systematic cultivation of insight. Insight which leads to a fundamental transformation in our existential mode.

The structure of attention

Transparency/opacity of objects

In The Tacit Dimension, Michael Polanyi points out that attention has a really important underlying structure.

This stuff can be a bit abstract.

Let’s try to demonstrate it with a physical example, of “investigating” an object with a “probe”.

Pick up an object like a glass and place it next to your monitor. This is going to be our primary object of investigation.

Pick up a pen or pencil. This is going to be our probe.

Start tapping the object with the probe, and try to notice things about the object. For example, its shape, density, the sound the probe makes when it comes into contact with the object, etc.

For maximum effect, close your eyes while you’re tapping, and focus on the object.

Do this for ~30 seconds.

Tapping on the object starts to form an image of it in our mind. Until now, the focus of our attention has been totally on the object. When you’re ready, try the following:

Keep tapping. But instead of focusing on the cup try focusing and investigating the nature of the probe. Try this with your eyes closed for ~30 seconds.

Keep tapping, but try to notice the sensations on your fingers as you’re tapping the probe. Try this with your eyes closed for ~30 seconds.

Most people can perform some version of this exercise. When most of us focus on our fingers, the cup starts to melt away. When we focus on the cup, the fingers often melt away.

When we’re focusing on the cup, our fingers and the probe are “transparent” to us, and the cup is “opaque” to us. That is, we’re looking through our probe into the cup. This is similar to how our glasses are often “transparent” to us, in that we look through the lenses to look at an “opaque” world. But this transparency/opacity is fluid. We can take off our glasses and inspect them, instead of inspecting the world through them. That is, we can make our eyes “transparent” and the glasses “opaque”. Similarly, we can gradually turn the probe and our fingers opaque, even though they started off transparent within the exercise.

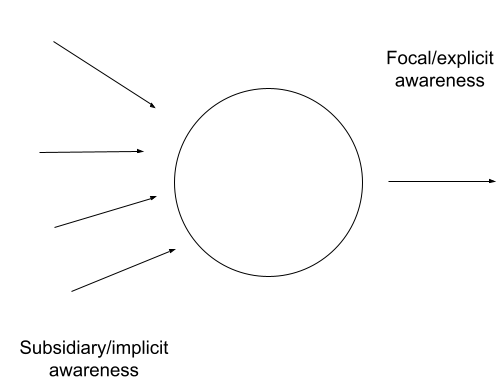

When we’re using the probe to know the cup, we have a subsidiary or implicit awareness of it. We look through the probe to maintain a focal or explicit awareness of the cup. But we also have the ability to transition the subject of our implicit and explicit awareness, to prioritise a particular object. When the cup is our focus, our mind is still processing some sensations from the probe and the fingers. But we’re only consciously aware of what’s currently being prioritised and optimised for.

This structuring of attention is totally ignored by the “spotlight” metaphor of attention.

When we interact with the cup, we’re “integrating” with the probe to conform to the nature of the cup. That is, our attention is structured so that we have the ability to integrate technologies that are “external” to our bodies to facilitate our investigation. In fact, we’re constantly doing this all the time. Consider the psychotechnology of literacy. We’re so accustomed to being literate that we don’t really look “at” it anymore. Our default is to look “through” literacy. But by no means is it a default of human cognition. Children need to spend many years learning literacy. It’s a relatively recent invention during our evolutionary history.

Going from features to the gestalt

Consider the following words:

The symbols associated with the H and the A in “THE” and “CAT” are almost visually identical. However, we can instantly disambiguate them. But there’s a problem of recursion here. In order to read the words, we need to have first read the individual letters. But in order to have read each individual letter, we need to have first read the whole words. This recursion would naively imply that reading is impossible! But of course, reading isn’t impossible. The spotlight metaphor of attention can’t address this.

Attentional processing is simultaneously top-down and bottom-up. Our cognition takes lower level “features” and starts to put them together to form a “gestalt” of what we’re perceiving. But this “gestalt” is also passed back down to better perceive and update the underlying features. Our cognition is constantly engaged in this dynamical process of feedback. It’s doing this during each second of our lives.

Putting it all together

Not only is our attention constantly doing this top-down/bottom-up processing, it’s also helping us seamlessly shift between the transparency/opacity of objects based on our goals.

These two processes are happening independently, all the time. Note that just as objects can shift between being transparent and opaque, features/gestalts are also on a continuum. That is, things that used to be the gestalt can end up being features for a higher-level processing. For example, imagine if “THE CAT” from above was actually part of the sentence “THE CAT IS CUTE”. “THE CAT” would then be a feature for the overall gestalt that is the sentence. There are no absolutes here. It’s all relative. Our attention is constantly shifting between all of these in a process of optimization.

Although we can understand each axis independently, they’re almost always operating in a coordinated fashion. For example, we can see this play out in the way we do science. As we go up from features towards an ever larger gestalt, more of the world starts to become visible to us. If we understand that objects have mass, acceleration and force, we seek to integrate these qualities together. Similarly, there’s a pattern of reducing things down to find their most primitive constituent pieces. We can refer to the two as “scaling up” of attention or “scaling down” of attention.

When we’re taught to meditate, we’re often told to focus on the breath with a soft attention that renews our interest in the object. For example, we’re asked to pay attention to the feelings and sensations in the abdomen, the tip of the nose, etc. We don’t normally pay much attention to these sensations in our body. We often look through these sensations rather than at them. As the diagram above shows, meditation teaches us to “scale down”. It teaches us to look at increasingly finger-grained features and ever deeper layers of our sensations.

What happens if we maintain a practice of continuing to scale down? We get to a specific kind of mystical experience that Robert Forman calls the Pure Consciousness Event. What does it feel like? Well, let’s go back to our example with the probe and the cup. We saw that it was possible to go from the cup, to the probe, to the sensations in our fingers. There are meditative practices that can help us continue this process of stepping back until we’re just looking at our consciousness, rather than through it. In this state, we’re not really conscious of anything, we’re just conscious. We’re not aware of ourselves, since we’re not looking through the machinery that constructs our “identity”. We’re just conscious. Some states of jhana in Buddhism involve what’s being described here.

What happens if we maintain a contemplative practice of scaling up? “Meditation” means to “focus towards the center”. This is actually in contrast with the word “contemplation”. Its etymology comes from “temple”. That in turn comes from “templum”, which means an open space where people gaze up to get signs from the gods. To contemplate is to look up towards the divine. The cultivation of loving-kindness is a contemplative practice from Buddhism. Experienced Buddhists often talk about how they perceive everything as interconnected, flowing and impermanent. They’ve created such a large overarching gestalt that they experience this empathetic resonant at-onement with the world. It’s sort of like being in a flow state that encompasses their entire perception of reality.

But ultimately, we want to put the two together. Notice that these practices of scaling up and scaling down need to be balanced with each other. If we continue to scale up without any sort of correction, we can get maladaptively “locked” into a gestalt. If we continue to scale down without any sort of correction, we can freeze with confusion because we’ve got no overarching narrative to tell us what to do next. The two need to work in unison in what John calls “opponent processing”. This is similar to the nine dots problem. We can’t solve the nine dot problem, until we scale down to break our previous erroneous gestalt, and scale up to find one that can solve the problem.

This is similar in spirit to what the musician from the Buddha’s myth said. The string can’t be too tight, nor can it be too loose, nor can it be some middling compromise. It needs to be just right.

When we practise the ability to really push our scaling up and scaling down, we can reach a state of non-duality. In the Mādhyamaka Prāsaṅgika school of Mahayana Buddhism, this state is called the direct perception of emptiness. In this state, we’re not just a pure consciousness nor are we at-onement with the whole world. We’re in a state that transcends both. In this state, we’re not trying to solve anything trivial like the nine dots problem. We’re trying to gain insight into the fundamental nature of our agent-arena relationship. We’re scaling down to the ground of our agency as much as possible, and scaling up to the circumference of our arena as much as possible.

This insight is how we can “re-member” the being mode. This is the radical transformation that was on the path to Siddhartha’s “awakening”. Think about what it’s like when we meet someone that seems to be in the flow state all the time. They have a certain grace, energy and it shows on their face. What would it be like to interact with a person that’s in such a state all the time?

There’s even a sutta that captures this aspect of the Buddha.

On one occasion the Blessed One was traveling along the road between Ukkattha and Setabya, and Dona the brahman was also traveling along the road between Ukkattha and Setabya. Dona the brahman saw, in the Blessed One's footprints, wheels with 1,000 spokes, together with rims and hubs, complete in all their features. On seeing them, the thought occurred to him, "How amazing! How astounding! These are not the footprints of a human being!"

Then the Blessed One, leaving the road, went to sit at the root of a certain tree — his legs crossed, his body erect, with mindfulness established to the fore. Then Dona, following the Blessed One's footprints, saw him sitting at the root of the tree: confident, inspiring confidence, his senses calmed, his mind calmed, having attained the utmost control & tranquility, tamed, guarded, his senses restrained, a naga.[1] On seeing him, he went to him and said, "Master, are you a deva?"[2]

"No, brahman, I am not a deva."

"Are you a gandhabba?"

"No..."

"... a yakkha?"

"No..."

"... a human being?"

"No, brahman, I am not a human being."

"When asked, 'Are you a deva?' you answer, 'No, brahman, I am not a deva.' When asked, 'Are you a gandhabba?' you answer, 'No, brahman, I am not a gandhabba.' When asked, 'Are you a yakkha?' you answer, 'No, brahman, I am not a yakkha.' When asked, 'Are you a human being?' you answer, 'No, brahman, I am not a human being.' Then what sort of being are you?"

"Brahman, the fermentations by which — if they were not abandoned — I would be a deva: Those are abandoned by me, their root destroyed, made like a palmyra stump, deprived of the conditions of development, not destined for future arising. The fermentations by which — if they were not abandoned — I would be a gandhabba... a yakkha... a human being: Those are abandoned by me, their root destroyed, made like a palmyra stump, deprived of the conditions of development, not destined for future arising.

"Just like a red, blue, or white lotus — born in the water, grown in the water, rising up above the water — stands unsmeared by the water, in the same way I — born in the world, grown in the world, having overcome the world — live unsmeared by the world. Remember me, brahman, as 'awakened.'

https://www.accesstoinsight.org/tipitaka/an/an04/an04.036.than.html

By being awakened, the Buddha moved past an identity he could have, to a fundamental way of being. That’s why even the category of “human being” was incorrect. Rather, he seemed to exist beyond the need to possess an identity aligned with any such categories or views. He fully and deeply sati’ed (i.e. remembered) the being mode. He got a fundamental insight into what it means to be a human being.

Altered states of consciousness

When people normally enter altered states of consciousness (e.g. their dreams) and come back to the waking world, they’re insistent that the dreams were fake and their default mode is what’s real. But sometimes (e.g. via meditation/contemplation or psychedelics), people enter altered states that offer them deep insight. They become convinced that the world they briefly glimpsed within those states is what’s “real”. Everything else in their mundane experience is what’s actually “fake”. Just like the parable of Plato’s cave, they come to believe that this is the world of shadows and echoes. And just like that same parable, they find it difficult to describe what they saw to denizens of the cave.

We have an underlying meta-drive to be connected with reality as much as possible. So when we get these powerful insights, we’re overtaken with a need to transform our lives to sati/re-member that feeling of connectedness. Our whole agent-arena relationship becomes fundamentally transformed. William Miller and Janet C’de Baca call this a quantum change.

Moreover, these experiences of insight seem to be universal across human populations and cultures. Studies have shown strong correlation between people’s ability to experience meaning in their lives, and outcomes of wellbeing.

This quantum change is so axial. We could argue that all the major world religions are built on the foundation of adaptively altering our consciousness to gain insight. We’re not saying that all the major religions have the same beliefs. Studies show that it doesn’t seem to matter what the content of these mystical experiences is. Very often, there’s no content because they’re ineffable. But it seems that within those experiences, we’re somehow optimising our capacity to make meaning, and our process of anagoge.

John Vervaeke isn’t advocating nor proselytizing Buddhism here. Neither am I. But it does seem that there are deep connections between the structure of attention, mindfulness and the enhancement of our ability to enter these higher states to alleviate existential distress.

The next few episodes dive deeper into providing an account of consciousness, and an exploration of these higher states of consciousness.