Episode 3 - Continuous Cosmos and Modern World Grammar

Awakening from the Meaning Crisis

Episode 3 - Continuous Cosmos and Modern World Grammar

A lot of the material in the last episode was to foreshadow a deeper description of the Axial Revolution. That’s what this episode is about.

The Axial Revolution was a fundamental change in the structure of the mythologies and associated psycho-technologies that people used to parse their reality, into an axis-like structure. Wow. That was an intimidating mouthful. But it’s okay! We’re going to take it apart piece by piece.

What’s a mythology anyway (in the way we’re going to use the term)?

“Mythology” in popular culture often evokes the idea of a foolish or antiquated falsehood that people believe about history. That’s not at all how we’re going to use the term.

Myths are symbolic stories about recurring patterns that seem to pop up again and again in human civilization. They’re an attempt to take intuitive, implicitly learned patterns (see the last episode), organised via metaphor into a form that can be easily shared with other people. Myths are symbolically true but they’re rarely objectively true. For example, consider a really famous play Romeo and Juliet. The play is fiction, and the events within it are not objectively true. However, the play explores themes that society finds deeply compelling. Otherwise we wouldn’t subject high school students to write essays about it. There wouldn’t be thousands of academic papers written about Romeo and Juliet. The play is true in a symbolic sense. That is, the play contains literary observations about the human condition, and the sorts of situations that we tend to find ourselves in.

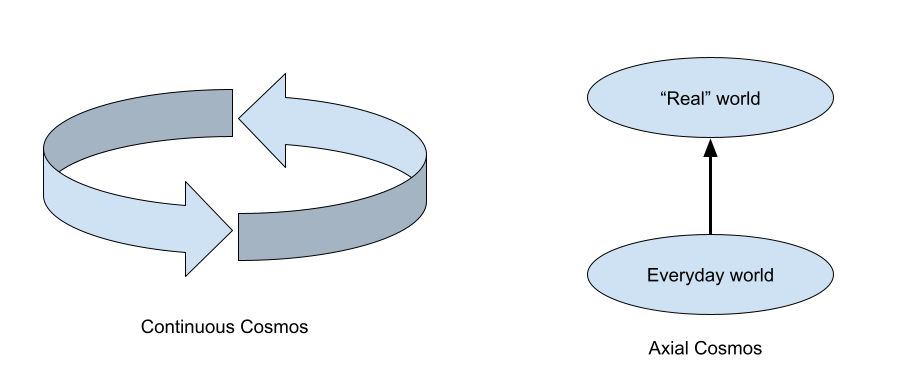

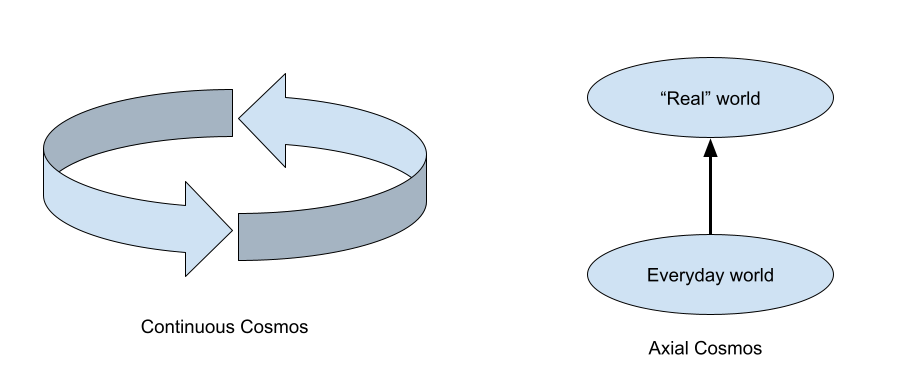

The continuous cosmos

The predominant pre-axial age mythology is something Charles Taylor calls the “continuous cosmos”. There’s traces of this mythology in a lot of modern traditions. But it’s quite difficult for us to intuitively understand because it’s so alien to how we currently conceptualise the world. The people that acted out this mythology parsed themselves as being deeply connected to the world, with a radical sense of continuity. They didn’t see a separation between the natural world, the cultural/material world and the divine world. When most people today look at a rat on the NYC subway, they see themselves as being fundamentally different to a rat. A rat is a different “kind” of creature and there’s something fundamentally special about humans that separates us from them. The inhabitants of a continuous cosmos mythology wouldn’t have perceived the rat that way. To them, all living creatures would have been participants of a symbolic “cycle”. The key differentiator between you and the rat would have been the power you possessed to influence the world around you. It wouldn’t have been weird to conceptualise rats that can talk, animals with complex societies or for a human to be a god. For example, the Pharaoh was worshipped as a living god-king. Today, it’s really hard to wrap our heads around that. But it wasn’t merely metaphorical for the Egyptians. He was actually their god. Why? Because this is a cosmos where reality is experienced primarily through the lens of power. It’s a mythological structure where there isn’t anything necessarily “special” about humans. Acquiring wisdom in this world involved acquiring power to improve outcomes for your people, and fitting in more deeply into the cosmos.

Such a world was continuous in another important way. Time was cyclical and moved in large cycles that spanned eternity, just like the weather or night and day. In this world, your ritual behaviour is designed to somehow re-enact and harness the original power of creation. A power which you can then use to improve your own life. You want to stay deeply connected to the world, but don’t want to change it around too much. Because if you make drastic changes, you’re actually changing your “past”. Conceptualising time in this cyclical way is incredibly foreign to us today. In this world, there’s a deep continuity between the natural world, the social world, the divine world, as well as the past, present and future.

The Axial Worldview

The axial revolution shattered this mythological structure to give us something we’d find more familiar today. The last episode discussed how humans exapted their newfound skills at second-order thinking and abstract logic to realise their capacity for self-deception. The axial revolution took this one step further by breaking up the continuous cosmos into a mythology of two worlds. The first world was the “everyday world” beset by self-deception, violence and tragedy that until then was considered the natural order of things. The second world was the “real world” that humans could inhabit if they overcame the foolishness of their everyday world, and lived their lives wisely.

Wisdom was no longer about merely acquiring power and fitting in more deeply into the world, as it was in the continuous cosmos. In the axial worldview, it’s not actually desirable to fit in more deeply into the everyday world. One wants to gain the wisdom to rise up and transform oneself out of this world into the “real world”. It’s implying that we’re somehow strangers in our own world, seeking wisdom to rise above it. In the axial world, one’s increasingly defined by one’s ability to grow past their own foolishness and limitations. That language is still pervasive today. People really care about “personal growth”, and want to associate with people that have “grown up” above their childish foolishness.

Also note that there isn’t a hard cutoff between mythologies that have one structure versus the other. Instead, we see an evolution over time where these two ideas describe different points on the same spectrum.

What is the “meaning crisis”?

We haven’t yet covered enough material to properly discuss the “meaning crisis”. However, what we’ve covered by now already foreshadows some of it.

Mythologies with an axial structure have led to the development of many psychotechnologies that our societies have been built around. However, this axial structure is becoming less and less viable for us. Partly due to the scientific revolution, it’s difficult for us to conceptualise reality in terms of a “fallen” world that we currently inhabit and the “real world” that we need to transcend to. Earlier in this post, I mentioned that many people believe that there’s a deep and fundamental difference between a person and a rat on the NYC subway. With every passing year, the scientific worldview makes inhabiting an axial worldview increasingly difficult. For example, both the rat and a human are mammals, after all. We’re both shaped by evolutionary processes. We both have similar innate drives, and perhaps our difference is merely a difference in biological complexity, etc etc. Ironically, the scientific worldview is returning us to some version of the continuous cosmos.

Our psyches find themselves between rock and a hard place. On the one hand, our culture, laws, and institutions have an implicit assumption around an axial mythological structure and their associated psychotechnologies. But the knowledge we’re slowly accumulating about the world via the scientific revolution is making this underlying structure less viable. We don’t want to lose everything we’ve gained through the axial revolution. But the destination we’re going to isn’t immediately clear. I suspect that this is related to the increased interest in the West in Buddhist ideas. Superficially, Buddhist mythology with its emphasis on empirical examination is very compatible with the scientific worldview.

Subscribing to a mythology isn’t just a question of whether a person subscribes to a list of statements about the world. It’s whether they’re capable of acting out the mythological structure in their day-to-day life.

Future lectures in this series dive deeper into this issue, once more essential concepts have been introduced. But this should give you a taste of what the “meaning crisis” actually is.

Axial Revolution in Ancient Israel

The Axial Revolution took place all over the world. However, we first need to turn towards the developments that took place in Ancient Israel. I’m not Jewish nor a Christian in the sense that I don’t actively practice in the rituals of those traditions. However, being a member of those traditions is irrelevant for the purposes of this discussion. If you’re living in a society developed or strongly influenced by the Judeo-Christian worldview, you’re acting out its worldview and you’ve implicitly learned its forms of thought. This is through cultural norms, legal norms, etc. Essentially, the degree to which someone in the West doesn’t grasp the grammar in the Bible is the degree to which they don’t understand the workings of their own cognition. Note that “grammar” isn’t what you say, it’s how you think and the structure your thoughts take. Even if you don’t live in the West, you should consider the degree to which your culture has been Westernised.

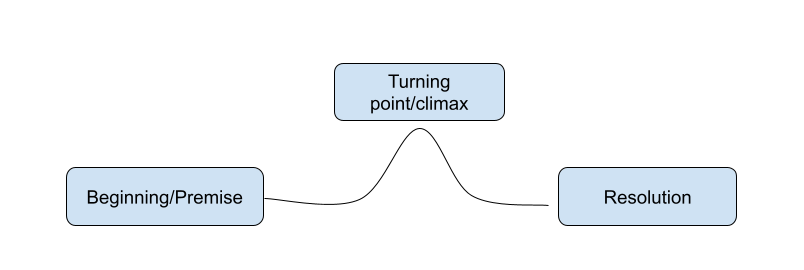

The grammar from the Bible is so ubiquitous in our popular culture that we don’t even notice it. For example, most movies you watch in the West involve a person “straying off the path” and committing some terrible mistake. The plot twists into a climax where the protagonist learns the error of their ways, and works to achieve redemption. That specific narrative structure is heavily influenced by the Bible.

Essentially, the Ancient Israelites developed the psychotechnology of understanding time as a cosmic narrative. They exapted the universal psychotechnology of storytelling, and applied the specific narrative structure described above in an attempt to understand time.

These stories start with some beginning, or premise. They progress through time as the protagonist navigates the world and eventually reaches some turning point, or climax. Some problems are solved, or some insight is gained and there's a resolution where the future is opened up.

This is a radical idea compared to the continuous cosmos. In that world, there’s no real notion of the “future”, in the way that we understand that term today. Time is cyclical and you’re condemned to repeat the cycle of life. The cycle itself is suffering and you want to achieve freedom from it. However, in the narrative worldview, the future is totally open. Your actions can change the future if you understand how to properly participate in it. The universe is constantly unfolding through time and you’re participating in that act of ongoing creation with the god of that mythological structure.

The pre-axial gods (e.g. of ancient Egypt), are gods of specific places, roles or functions. For example, a god of fertility, death or a specific river. These gods don’t necessarily have much of a moral arc attached to them. It’s almost like they’re symbolic descriptions of the power wielded by pieces of the world. However, the God of the Old Testament doesn’t seem to be bound in the same way. This God is synonymous with the idea of infinity itself.

Consider the Exodus from the Old Testament. God liberates the Israelites and sets them on a path towards a future that’s promised. Unlike the Egyptian gods, this God moves through space and time, and is a god of the open future. That’s why initially he has no name. Because to name something is to locate it, specify it and tie it down.

In this axial structure, today’s everyday world is the world we’re trying to transcend. And the “real world” is the future that’s promised which can be inhabited if society correctly (or morally) participates in the co-creation of that future alongside God. This overall narrative structure is deeply ingrained in how people today are unconsciously taught to parse the world. For example, you know that your life doesn’t unfold in neat theatrical acts from a play, or arcs in a movie. Yet, you find stories structured in this way deeply satisfying.

We’ve already alluded to the idea that there’s multiple forms of “knowing”. For example, one type of knowledge is holding a set of facts in your head. Another type of knowledge is something that’s deeply participatory in nature. Sort of like knowing “what it’s like” to see the world in a specific way. The Israelites had a word for this type of knowledge called “da’ath”. Today, we’ve largely forgotten that there are these multiple types of knowledge. The Bible will often talk about sexual intercourse with the verb “knowing”. For example, Adam “knew” his wife Eve. It confuses people because today because we don’t use sex as a metaphor for knowledge. However, there’s a participatory dimension to having sex with someone. It’s not knowledge you get about a person by merely observing facts about them. You’re participating in the experience of that person. You’re changing them while they’re changing you. You’re identifying with them, empathising with them, resonating with them until this story reaches some climax or turning point. And then you experience a resolution.

For the Ancient Israelites, “faith” was one’s sense of da’ath. It wasn’t “beliving things for no reason just because a book said so”. Their faith was their feeling that they’re participating deeply with reality and that this participation would lead their people to the promised future. Implicit in this worldview is whether one is making progress or not, whether one has reached a turning point, or whether one has strayed off the path. Such grammar is still relevant today. For example, when considering relationships or projects, you’ll often ask yourself - “Is this going on course? Is this growing? Is this the person I want to be, and what’s my sense of how I’m changing?” That’s your sense of da’ath.

Obviously, sometimes people make mistakes. People can realise that not only are they off-course, but that they’re dramatically off-course. That’s the basis of the word “sin”. In the New Testament, the translation of “sin” comes from an archery term of “missing the mark”. It isn’t merely doing something immoral. When you’re shooting a bow and arrow, you can’t just shoot directly where your eye tells you to look. Wind and other conditions might necessitate that you take careful aim so as to strike your target correctly. You have to have the “faith” to have the sense to shoot it correctly so that you won’t miss the mark. It’s the idea that you're constantly trying to sense the course of your own life, and if you’re deluded or self-deceptive you won’t strike the target correctly.

Sometimes enough people can miss the mark so profoundly that God has to periodically intervene to “wake people up”. To show people how they’ve morally missed the mark, and have reached a turning point. This is the prophetic tradition in the Old Testament. A prophet in this context isn’t necessarily someone that predicts the future via supernatural powers. It’s someone that identifies how you’re off course right now, and wakes you up. It’s like a therapist that gives you the “oh shit!” moment, that wakes you up to your delusions and self-deception.

Think about how you conceptualise yourself today. You start off as a person somewhere, you make a goal and then you try to orient yourself towards that goal. You want your life and your culture to “progress”. How would you conceptualise yourself if you couldn’t make use of this notion of “progress”? Or for example, how important it is for you to “live up to your promise”. You’re trying to transcend above your everyday problems into a promised future. It’s an idea that we’ve inherited from the axial revolution in Ancient Israel and it’s deeply ingrained in us.

The axial revolution took place in lots of different parts of the world, and they have their own flavours of this. But being aware of this mythological structure is particularly relevant to those living in the West.

Axial Revolution in Ancient Greece

A previous episode discussed the importance of alphabetic literacy in increasing cognitive capacity. The ancient Greeks seemed to have pushed this idea particularly far. Not only did they standardise the reading direction from left to right, they invented the idea of “vowels”. This substantially improved the ease of learning the language, making it more widely available. It also increased the rate at which information could be processed. Together, it enabled them to increase their ability to think abstractly and improve their problem solving skills.

Athens was the birthplace of direct democracy. The argumentative nature of direct democracy created incentives for people to improve their ability to think abstractly and capacity for rational thought. Competitive forces in this arena created incentives for the emergence of mathematics, natural sciences, etc.

Everybody has heard of “Pythagoras” because of his theorem for right-angled triangles. It seems that he might have belonged to a group of men that underwent shamanic training. For example, there are reports that he underwent a ceremony that involved isolating himself in a cave and undergoing a radical transformation. He seems to have discussed ideas similar to shamanic “soul-flight”, because he talked about the capacity of the mind to be liberated from the body and gaze more clearly at the world below. He made lots of mathematical discoveries like the octave in music, and other important proportions. He realised that the psychotechnology of rational thinking gave humans access to important patterns in the universe that we’re not directly aware of.

Pythagoras invented a lot of words we now take for granted. He actually invented the word “cosmos”, and used that to describe the universe. Many of you treat the two terms “uni-verse”, that is, one-verse and “cosmos” as synonymous. But they’re not. “Cosmetics” is related to the word “cosmos”. What do cosmetics do? They reveal the beauty of things. How beautiful and ordered they are. So Pythagoras had the idea that we can use music, mathematics and practices for these altered states of thinking to transcend the broken everyday world and to see it as the beautiful world that it truly is.

Closing thoughts

We’re starting to see that the grammar of our cognition is more complex than we would have otherwise realised. It seems that even if we don’t identify with a particular religious tradition, merely inhabing a society shaped by its worldview influences the way we parse the world.

The next episode explores the axial revolution in Greece in more detail.